Il était une fois et une fois il n'était pas

Aurélien Froment

25.05.2023 - 22.07.2023, vernissage 25.05.2023

en français plus bas

"Andrei, these aren’t films you’re making...

Conversation with my father, after the premiere of Mirror"**

Aurélien Froment has always questioned what differentiates and what connects the art of cinema and other art forms. His gesture, whether it be associated with photography or the installation of physical objects in the exhibition space, is driven by emotion. And it is through the senses, which become the very purpose of the works, that our relationship to language is questioned. Perhaps we are seeking, through new forms, to capture the invisible streams that shape our lives. A new form calls for a new ceremony, or to put it another way, the words that remain within us need rituals — forms capable of bringing them back to life. If a snippet of what we are looking for were given to us at the sight of one or a body of work, it would not be erased or forgotten. The artists’ rituals help us to do this. If we don’t know how to celebrate, we should let the artists show us how accessible the ritual (here, a language of silence and sound) is and how we are still capable of experiencing it.

CB : As soon as we enter the exhibition, the shadow of the projectionist who has marked Aurélien Froment’s formative years runs from one wall to the other. It is the shadow of a hand holding a torch and projecting a circle of light onto the monumental Apocalypse Tapestry of Angers that the artist has scrutinised, focusing on details rather than the whole work. Aurélien regularly explores unique and unclassifiable pieces (the Arcosanti site in Arizona, the Ideal Palace of postman Ferdinand Cheval and, more recently, Pierre Zucca’s set photographs) to establish his own work method. He narrates a work that functions as an admirable and yet impenetrable monument. With the set photographs taken by Pierre Zucca, Aurélien explores each image’s choreographic features and, by screening them, he associates them with a general movement so that they take the place of the films whose stories they interrupt. His whole body of work is a journey aimed at facilitating communication between human beings on a spiritual level. He makes the moment when the image becomes a revelation accessible, like the cave painting awaiting the fire of the torch to combine objectivity and mystery and to magically bring back to life what has gone. Once upon a time, differently, between two shots, there were invisible ideas and messages. Director Raoul Ruiz talks about the "absent fragment", the "hypnotic point" of "sublime boredom". He is referring to the fragments of a horse statue quickly reconstituted in his mind and yet escaping. He had to sacrifice the seven fragments of the horse before him in order to bring it back to life and, in the end, focus only on one of these fragments to make the horse appear entirely***.

This exercise of the "absent" fragment reveals the incompleteness that is specific to cinema. In this exhibition, Aurélien tames these interrupted segments in order to expand our vision by filtering the messages of an artwork whose polyphony organises other illusions of continuity. These illusions penetrate our inner ear, which is physically explored in his latest film. An ear to filter reality as when one dozes off. An ear to lose touch with reality, and move towards hypnotic distractions without losing sight of continuity.

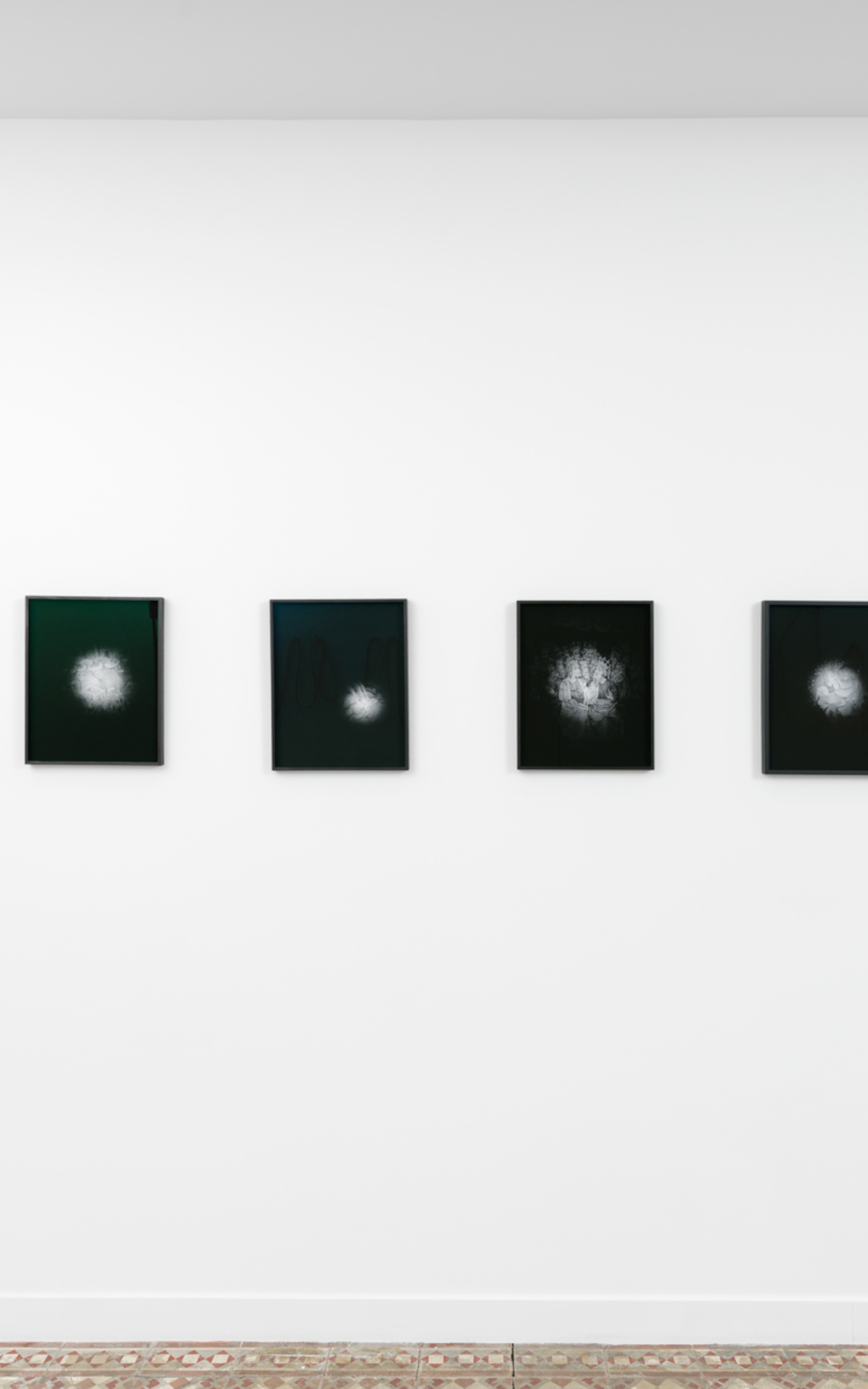

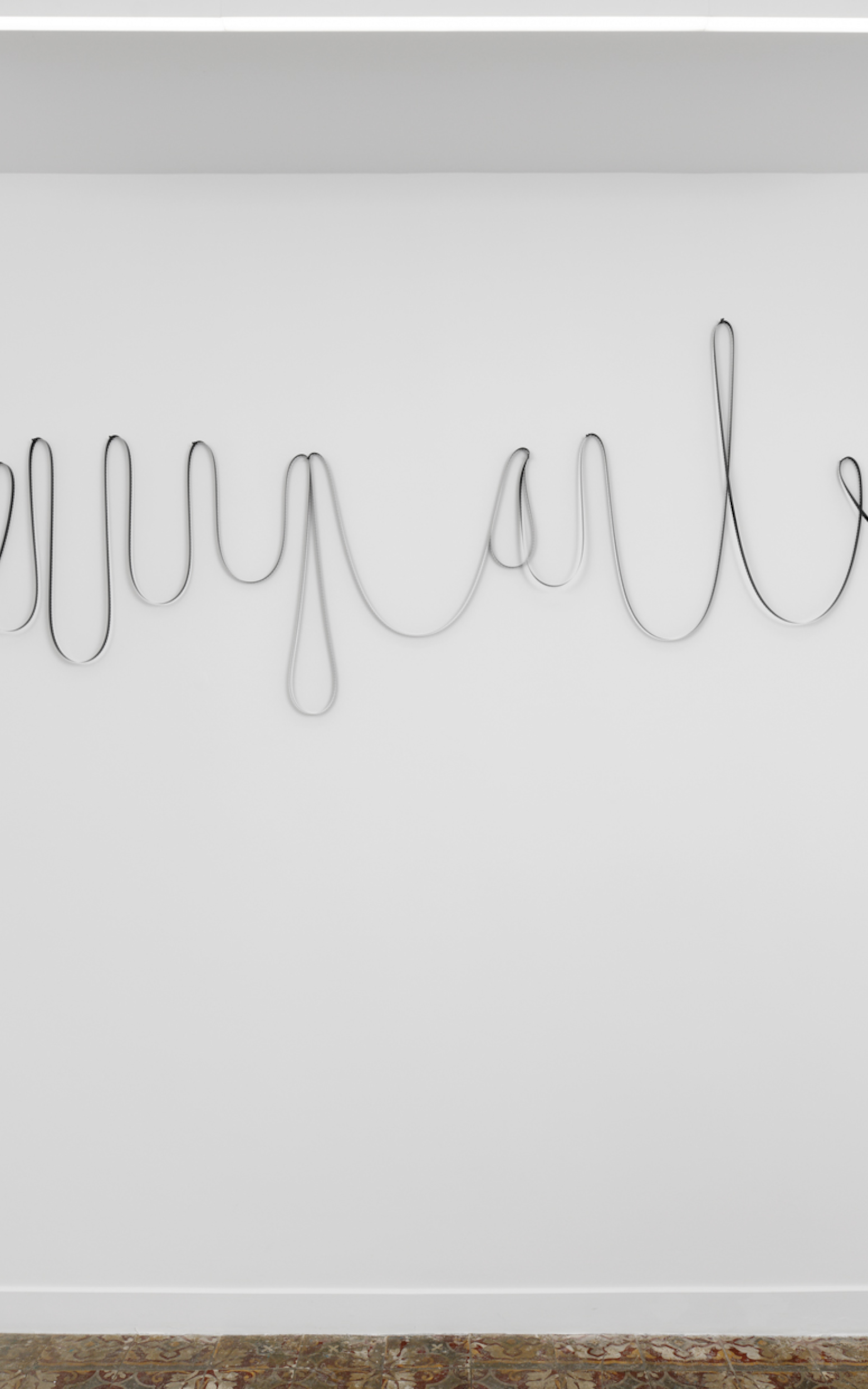

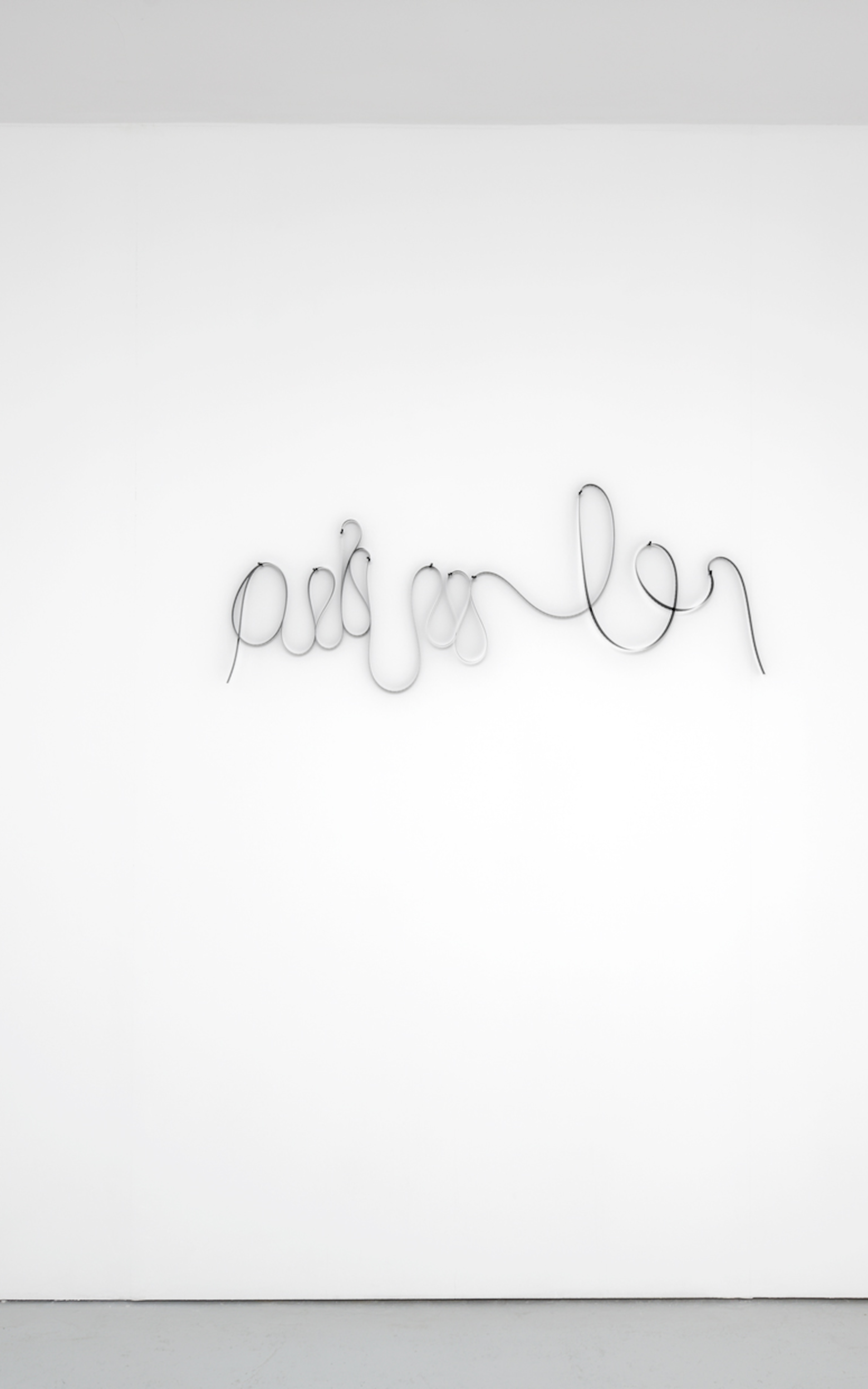

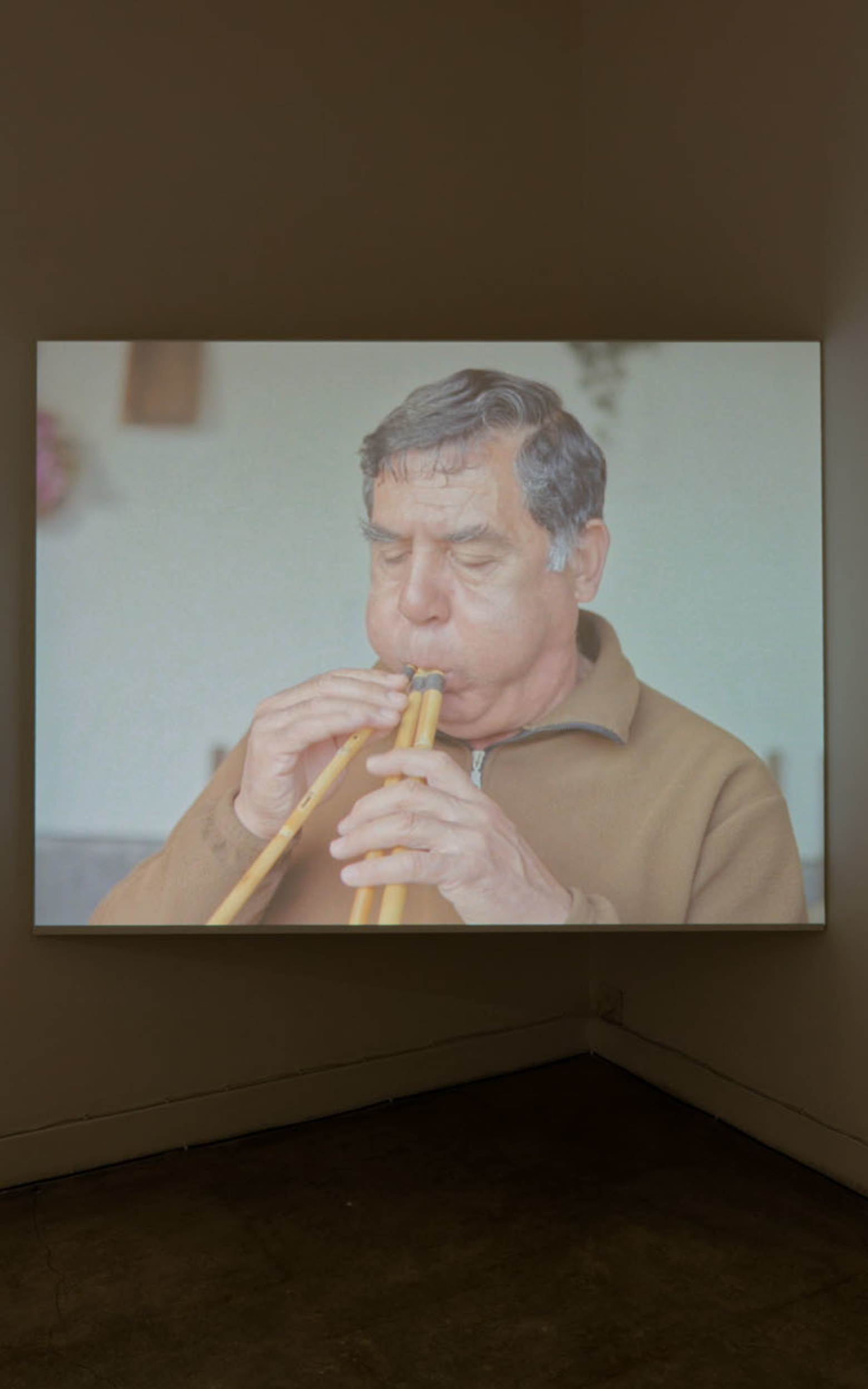

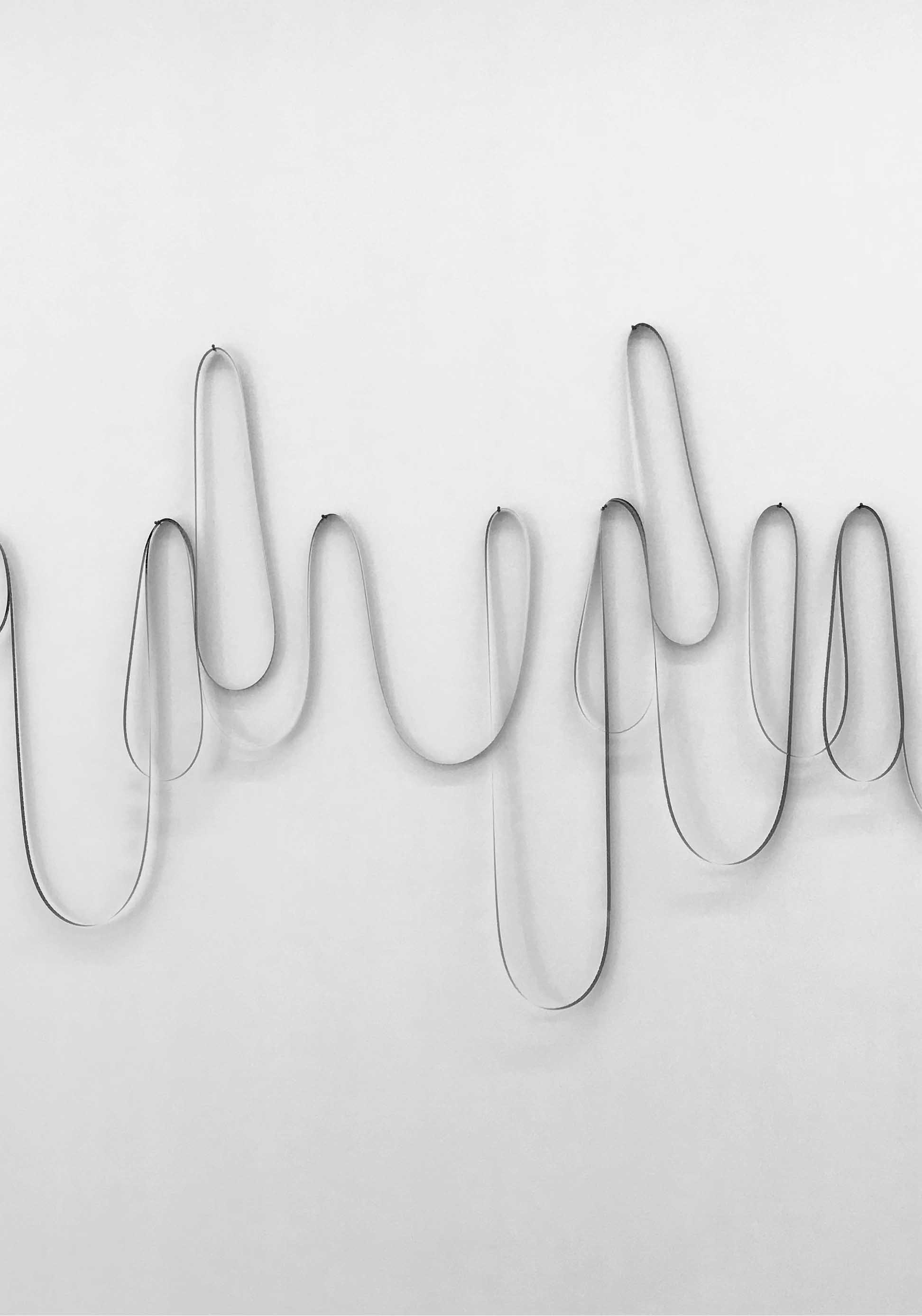

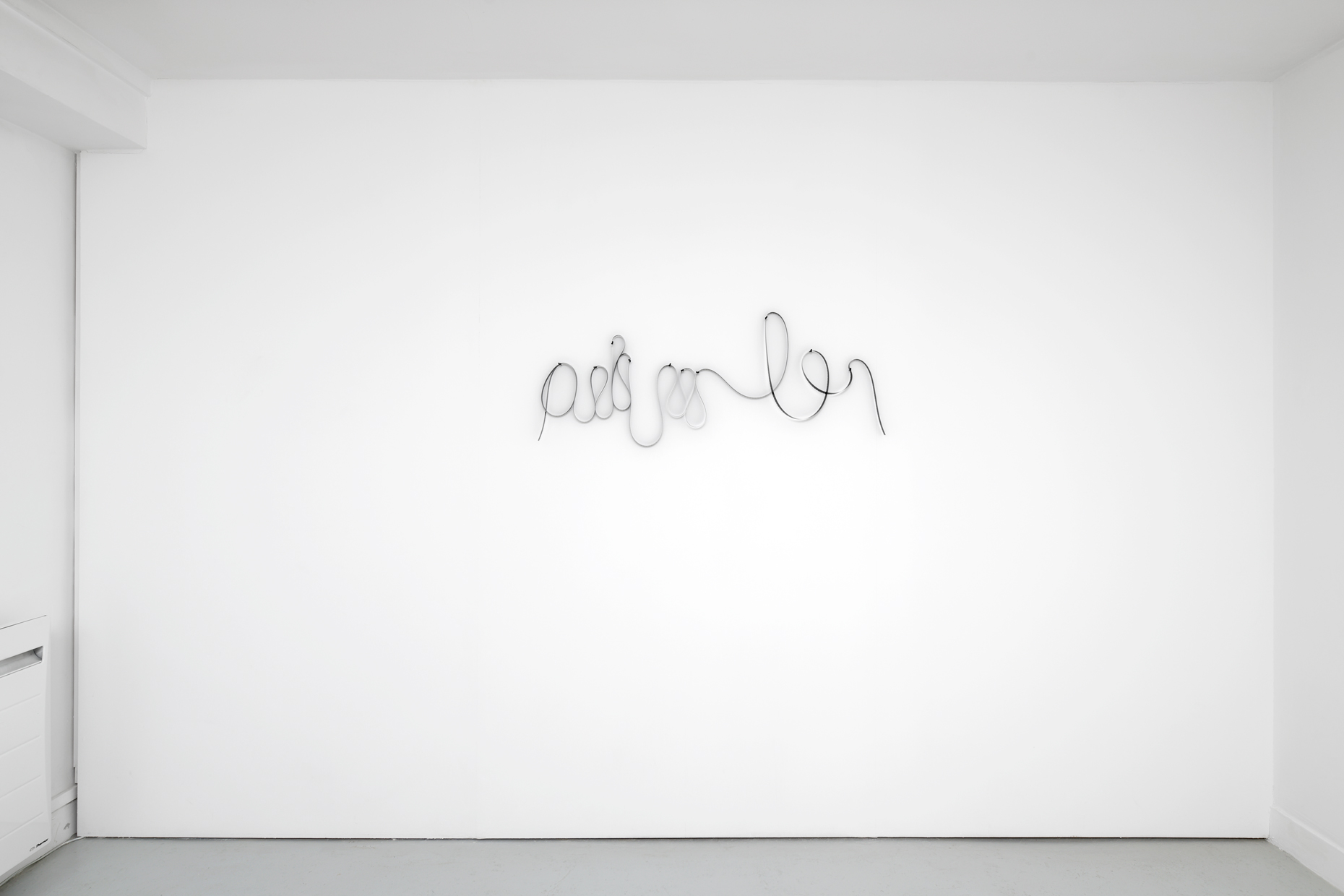

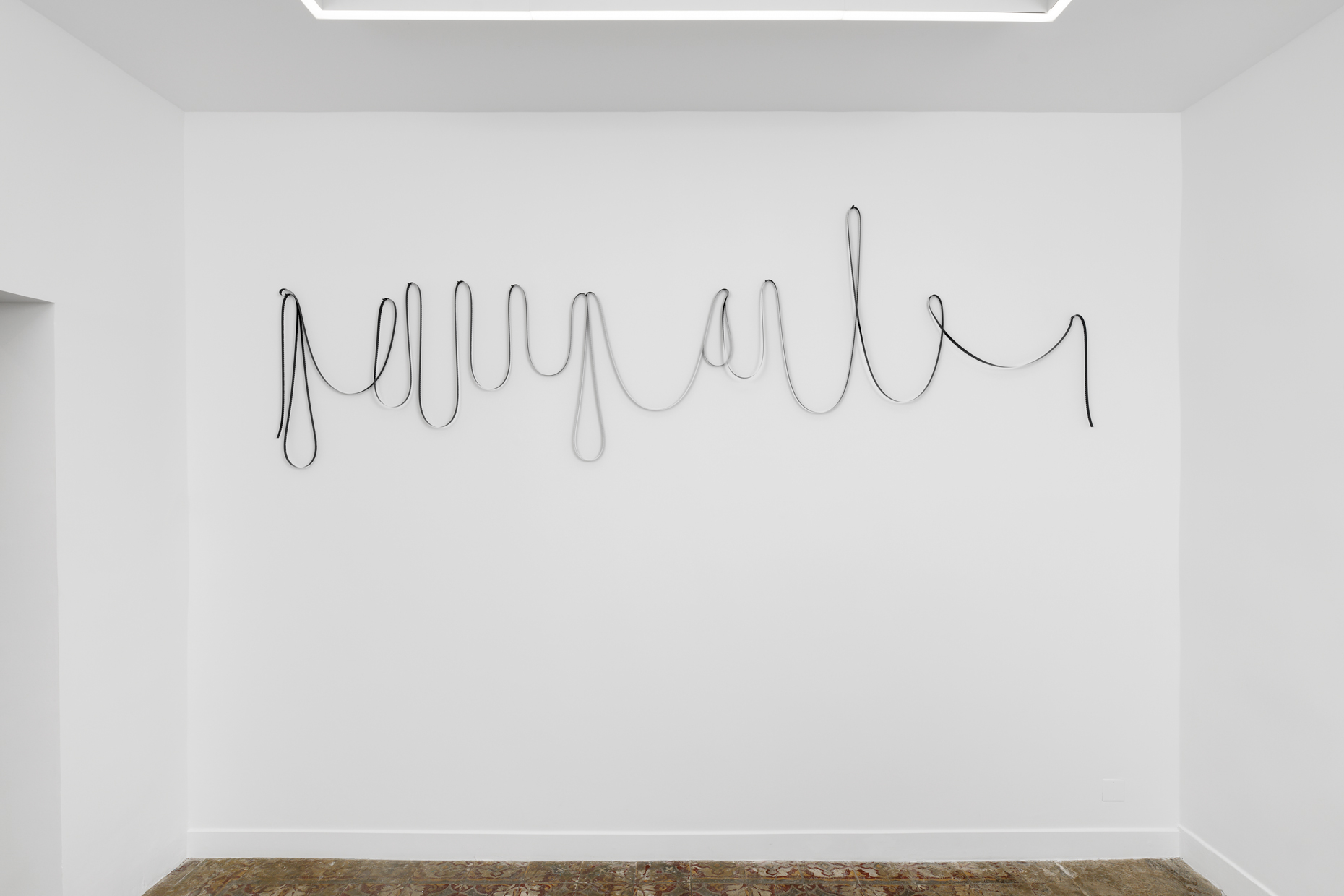

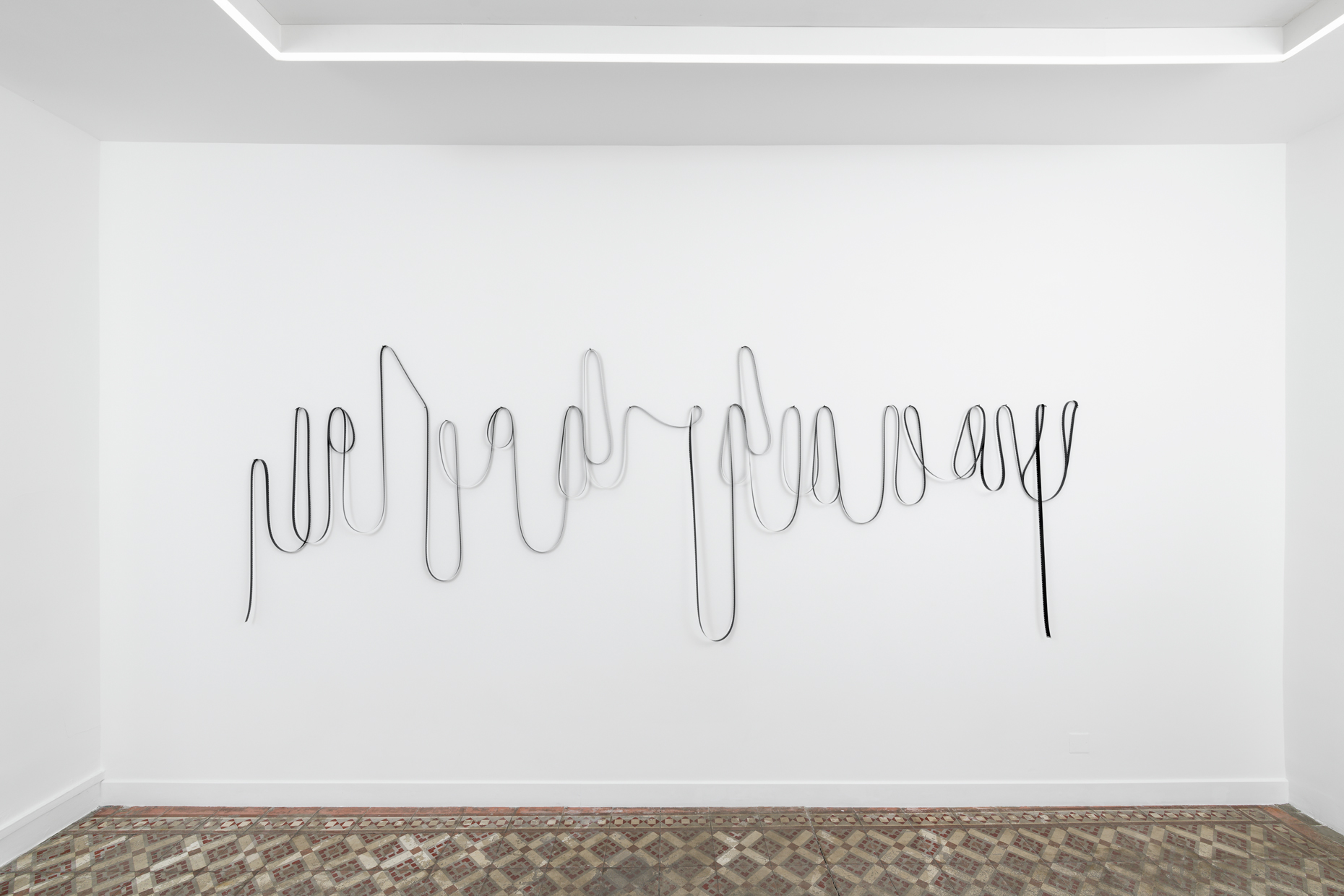

IA: The pursuit of some form of continuity between scattered fragments, the very image of our life experience, lies at the heart of each of Aurélien Froment’s exhibitions. For "œ" in 2018 at the gallery, the rope that was hand-dyed in a variety of colours and tied in several places thanks to sophisticated knots, provided this continuity — a real thread that introduced, through a physical experience, the performative thinking behind his film Apocalypse screened in the basement. Today, he returns to the images of the tapestry and it is the film roll running across the gallery walls that acts as a common thread between Amadou Badiane — the Senegalese singer who performs Main Bambai Ka Babu, a classic Bollywood song by Mohammed Rafi —, the film shot very close to inner ear specimens preserved at the University of Edinburgh, and Franco Melis, the Sardinian launeddas (wind instrument) player who closes the exhibition. The reel offers the same material and metaphorical action as the rope in the previous exhibition. Aurélien enjoys granting his works this double — real and linguistic — function, thereby undoing the binary nature of a rationalist view of the world that we are continuously resisting. Here, the breathing that animates the piece of reed or the vocal cords finds an ear that is embodied at the very bottom of the gallery.

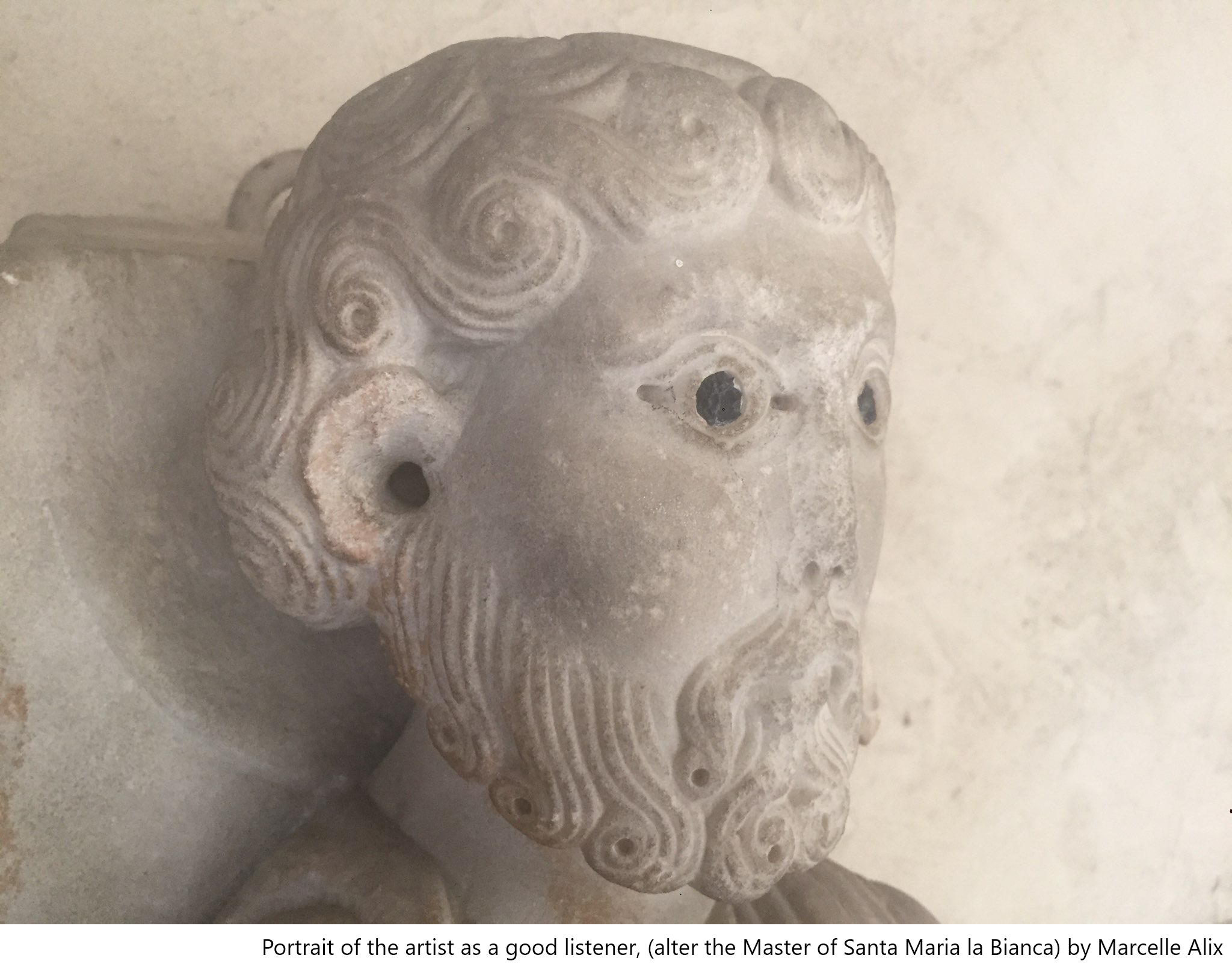

What I like about Aurélien’s work is his ability to look for all the possible ties between the different aspects of an exhibition: sensory, narrative, visual, and even philosophical. Over the years, he has drawn a resolutely modest figure of the artist: that of the projectionist, in charge of the images on the screen, and today that of the listener. These metaphors about the artist’s practice consist in collecting images and sounds, and patiently exploring the ways in which they are possibly inscribed within contemporary collective memory.

The title of the exhibition is drawn from Clarissa Pinkola Estès’s book Women Who Run with the Wolves: Contacting the Power of the Wild Woman, Arrow Books, 1998

**Andreï Tarkovski, Sculpting in Time, University of Texas Press, 1987

*** Raoul Ruiz, Poetics of cinema, Dis Voir, Paris, 1995

translation: Callisto McNulty

Aurélien Froment was born in France in 1976, he lives in Edinburgh (Scotland). Many institutions have organised solo presentations of his work, including M-Museum, Leuven, BE (2017), Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe, DE (2015), Villa Arson, Nice, FR, Le Plateau/ FRAC Ile de France, Paris (2014), Le Crédac, Ivry-sur-Seine, FR (2011), The Wattis Institute, San Francisco, US (2009), Gasworks, London, UK (2009), Bonniers Konsthalle, Stockholm, SW (2009), Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2008). He participated in the Sydney Biennial (2014), the Venice Biennial (2013), the Lyon Biennial (2011) and the Gwangju Biennial (2010).

His project Pierre Zucca/ Théâtre Optique which was initially presented at Institut pour la photographie in Lille in 2021 will be shown, in an extended version, at Rencontres Photographiques d'Arles during the summer 2023.

With the support of the Centre National des Arts Plastiques, Creative Scotland, Edinburgh College of Art and Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop.

Warmest thanks to: Emilie Notéris for the quote by Clarissa Pinkola Estès from her book "Wittig" (Éditions Les Pérégrines, 2022). Thanks also to the Kadist Foundation (Émilie Villez), Thomas Meret (DUNE(S) Corporation), Clotilde Beautru, Romain Grateau, Esteban Neveu, Chloé Poulain and Josselin Vidalenc.

Aurélien Froment would like to thank Andy Moore, Malcolm McCallum and the Anatomy Museum of the University of Edinburgh.

--

« Andreï, ce ne sont pas des films que tu fais...

Conversation avec mon père, après la première du Miroir »**

Aurélien Froment interroge depuis toujours ce qui différencie et ce qui rapproche l'art cinématographique des autres expressions artistiques. Ses gestes, qu'ils soient du côté de la photographie ou de l'installation d'objets physiques dans l'espace d'exposition, privilégient l'émotion. Et c'est par les sens qui deviennent l'objet des œuvres elles-mêmes qu'est questionné notre rapport à la langue. Sans doute cherchons-nous par des formes nouvelles à capter les courants invisibles qui influencent nos vies. Une forme nouvelle réclame une cérémonie nouvelle ou pour le dire autrement les mots qui demeurent en nous ont besoin de rituels, de formes capables de les faire renaître. Si une bribe de ce que nous cherchons nous était donnée à la vue d'une ou d'un ensemble d’œuvres, cela ne serait ni effacé ni oublié. Ce sont les rites des artistes qui nous y aident. Si nous ne savons pas comment célébrer, laissons les artistes nous montrer à quel point le rite (ici un langage du silence et des sons) est accessible et combien nous sommes encore aptes à le vivre.

Le réalisateur Raoul Ruiz parle de « fragment absent », de « point hypnotique » d' « ennui sublime ». Il fait allusion aux fragments d'une statue de cheval rapidement recomposée dans son esprit qui s'échappait pourtant. Il lui fallait sacrifier les sept fragments du cheval devant lui pour le faire revenir et surtout ne privilégier, au bout du compte, qu'un seul de ses fragments pour faire apparaître le cheval en entier***. Cet exercice du fragment « absent » rend visible l'incomplétude propre au cinéma. Dans l'exposition, Aurélien apprivoise ces segments interrompus pour agrandir notre vision en filtrant les messages d'une œuvre dont la polyphonie organise d'autres illusions de continuité. Ces illusions pénètrent notre oreille interne explorée physiquement dans son dernier film. Une oreille pour filtrer la réalité comme dans l'assoupissement. Une oreille pour perdre le fil de la réalité, tendre vers les distractions hypnotiques sans perdre de vue la continuité.

IA : la recherche d’une forme de continuité entre des fragments épars, image-même de notre expérience de la vie, est au cœur de chacune des expositions d’Aurélien Froment. Pour « œ » en 2018 à la galerie, la corde teintée à la main de couleurs variées et nouée en plusieurs endroits par des agencements savants offrait cette continuité, un fil réel qui introduisait par une expérience physique la pensée performative de son film Apocalypse projeté au sous-sol. Aujourd’hui, il retourne aux images de la tapisserie et c’est la pellicule de film courant sur les murs de la galerie qui fait office de fil rouge entre Amadou Badiane—le chanteur sénégalais qui interprète une chanson classique de Bollywood Main Bambai Ka Babu de Mohammed Rafi—, le film tourné au plus près de spécimens d’oreilles internes conservés par l’Université d’Edimbourg et Franco Melis, le joueur de launeddas (instrument à vent) sarde qui clôture l’exposition.

La bobine de film, « reel » en anglais, offre la même action matérielle et métaphorique, que la corde de l’exposition précédente. Aurélien aime attribuer à ses œuvres cette double fonction, à la fois réelle et linguistique, défaisant ainsi la binarité indissociable d’une conception rationaliste du monde à laquelle nous résistons sans cesse. Ici, le souffle qui anime le morceau de roseau ou les cordes vocales trouve une oreille matérialisée tout en bas de la galerie.

Ce que j’aime dans le travail d’Aurélien, c’est sa capacité à chercher toutes les correspondances possibles entre les différents aspects d’une exposition : sensible, narrative, visuelle, voire philosophique. Année après année, il dessine une figure résolument modeste de l’artiste : celle du projectionniste, chargé des images à l’écran, et aujourd’hui celle de l’auditeur. Ces métaphores du métier d’artiste consistent à collecter images et sons, à explorer patiemment leurs possibles inscriptions dans une mémoire collective contemporaine.

** Andreï Tarkovski, Le temps scellé, Éditions Philippe Rey, Paris, 2014, p.7

*** Raoul Ruiz, Poétique du cinéma, Éditions Dis Voir, Paris, 1995, p.112-113

Aurélien Froment est né en France en 1976, il habite à Edimbourg (Écosse). De nombreuses institutions ont présenté son travail dans le cadre d’expositions personnelles, parmi lesquelles le M-Museum, Louvain, BE (2017), le Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe, GE (2015), la Villa Arson, Nice, FR, le Plateau/ FRAC Ile de France, Paris (2014), Le Crédac, Ivry-sur-Seine, FR (2011), le Wattis Institute, San Francisco, US (2009), Gasworks, Londres, UK (2009), Bonniers Konsthalle, Stockholm, SW (2009), le Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2008). Il a participé à la Biennale de Sydney (2014), la Biennale de Venise (2013), la Biennale de Lyon (2011) et la Biennale de Gwangju (2010).

Son exposition Pierre Zucca/ Théâtre Optique initialement présentée à l'Institut pour la photographie de Lille en 2021 sera montrée dans une version étendue aux Rencontres Photographiques d'Arles pendant l'été 2023.

Avec le soutien à une recherche artistique du Centre National des Arts plastiques, de Creative Scotland, de Edinburgh College of Art et de Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop.

Remerciements : à Emilie Notéris pour la citation de Clarissa Pinkola Estès tirée de son livre « Wittig » (Éditions Les Pérégrines, 2022). Merci également à la Fondation Kadist (Émilie Villez), à Thomas Meret (DUNE(S) Corporation), Clotilde Beautru, Romain Grateau, Esteban Neveu, Chloé Poulain et Josselin Vidalenc.

Aurélien Froment remercie Andy Moore, Malcolm McCallum et le Musée d'Anatomie de l'Université d'Edimbourg.