Pink Cloth

Ian Kiaer

09.09.2021 - 23.10.2021, vernissage 09.09.2021

en français plus bas

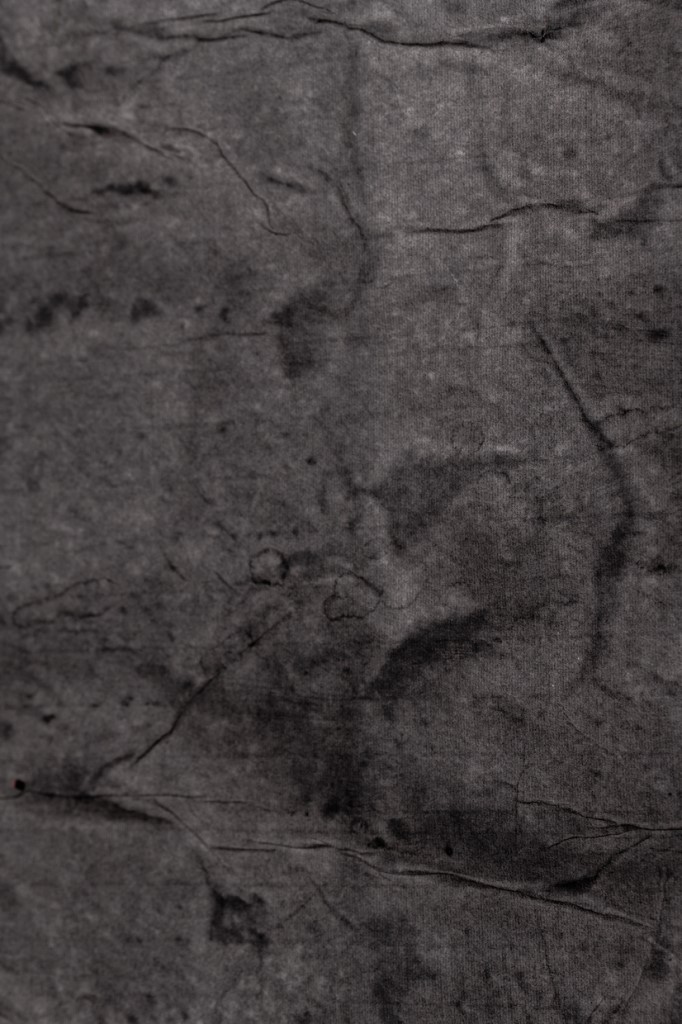

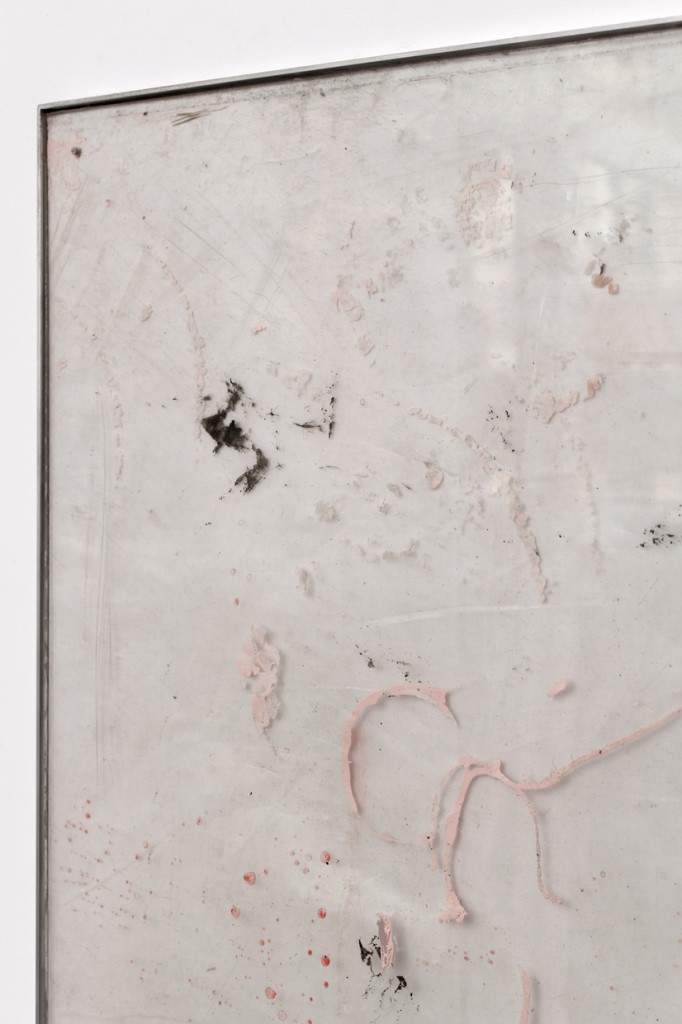

Like matsutake mushrooms, the Japanese species that thrives in the ruins of capitalism, Ian Kiaer's work has inhabited, since the early 2000s, the remnants of painting. His installations explore the ways in which what has been soiled, the scum, the accidental, what has been patched up, harvested, can be works of art.

The anthropologist Anna Tsing, in her book The Mushroom at the End of the World¹, describes the Anthropocene - which she calls the Capitalocene - as "a life without a promise of stability". In this world where precarity is the norm, where the idea of progress no longer manages to prevail, temporary arrangements of mineral, animal, plant and human lives settle within the ruins produced by capitalism. These unprecedented forms of collaboration are all but utopian. They originate from the here and now of the state of the world, forests devastated as a result of ruthless exploitation, the presence of communities displaced because of imperialist wars.

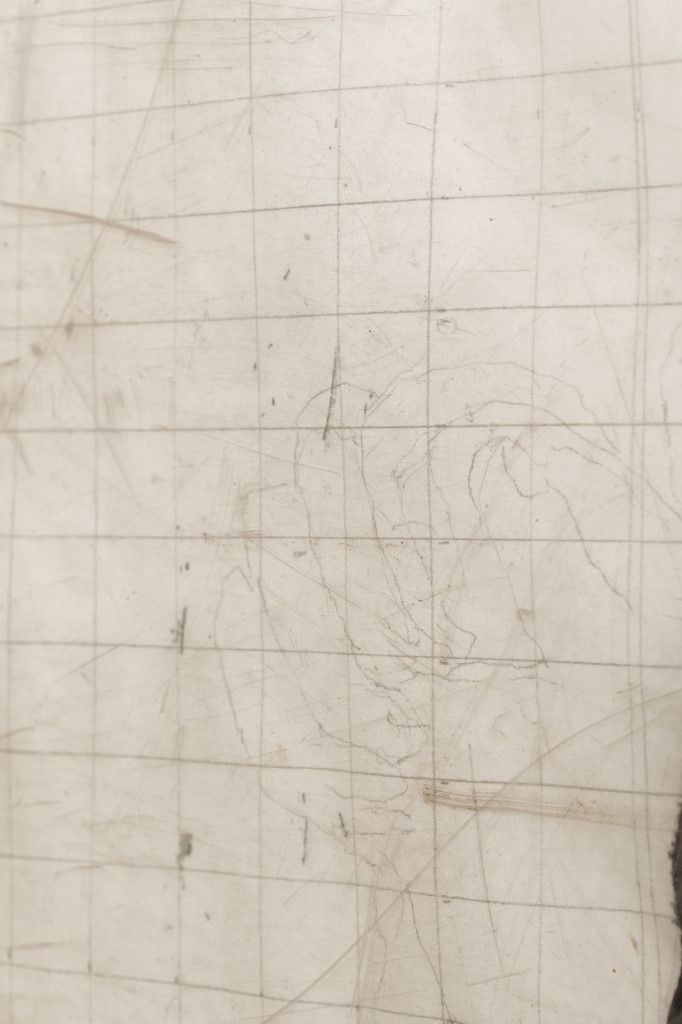

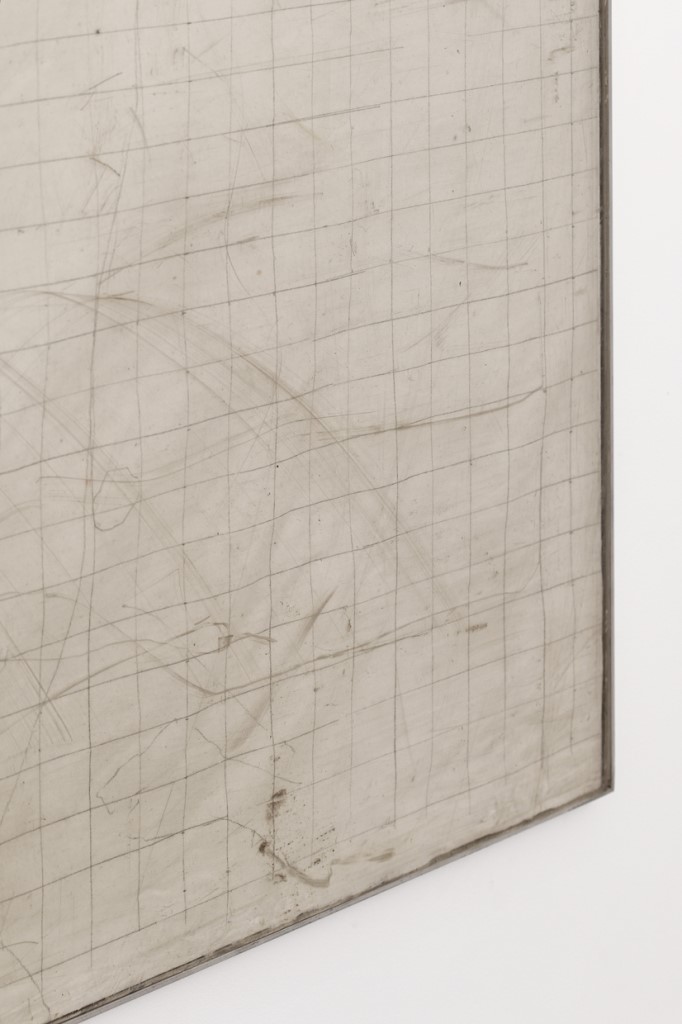

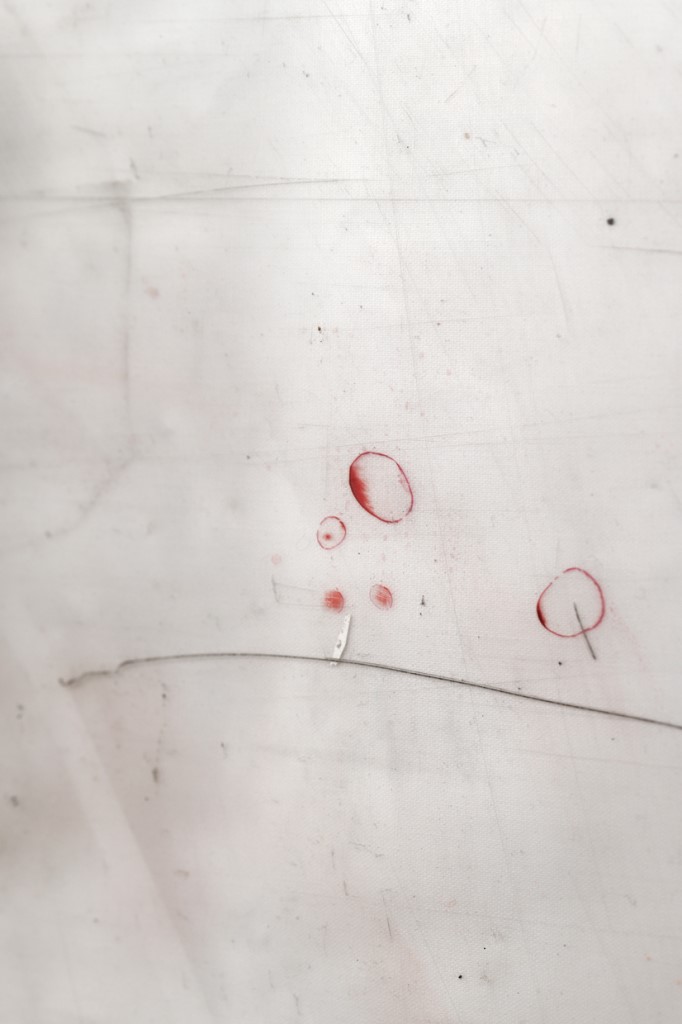

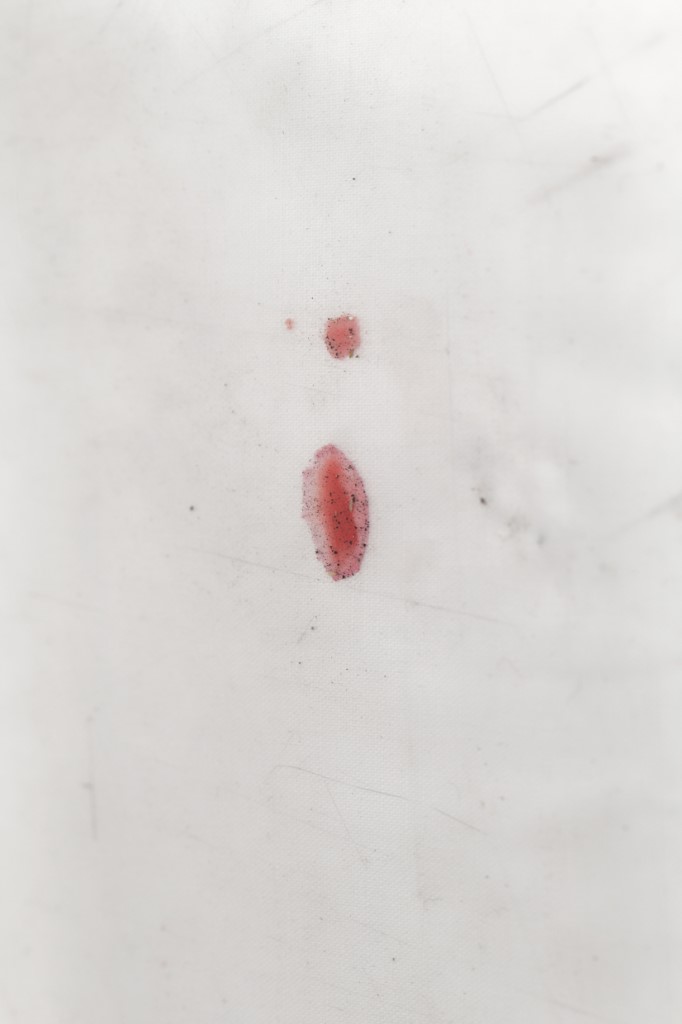

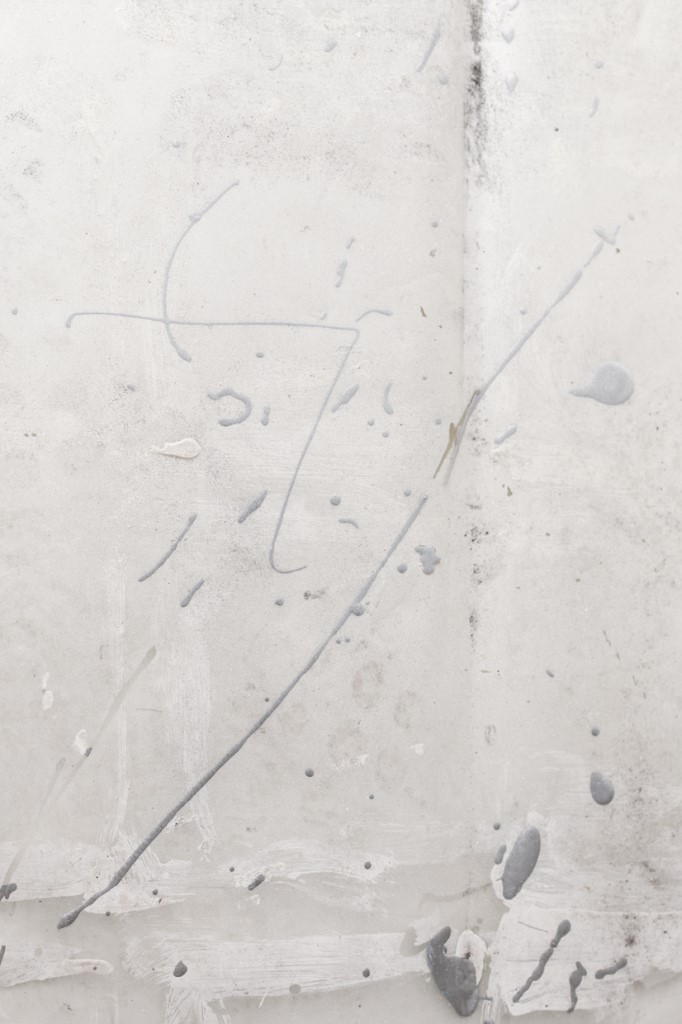

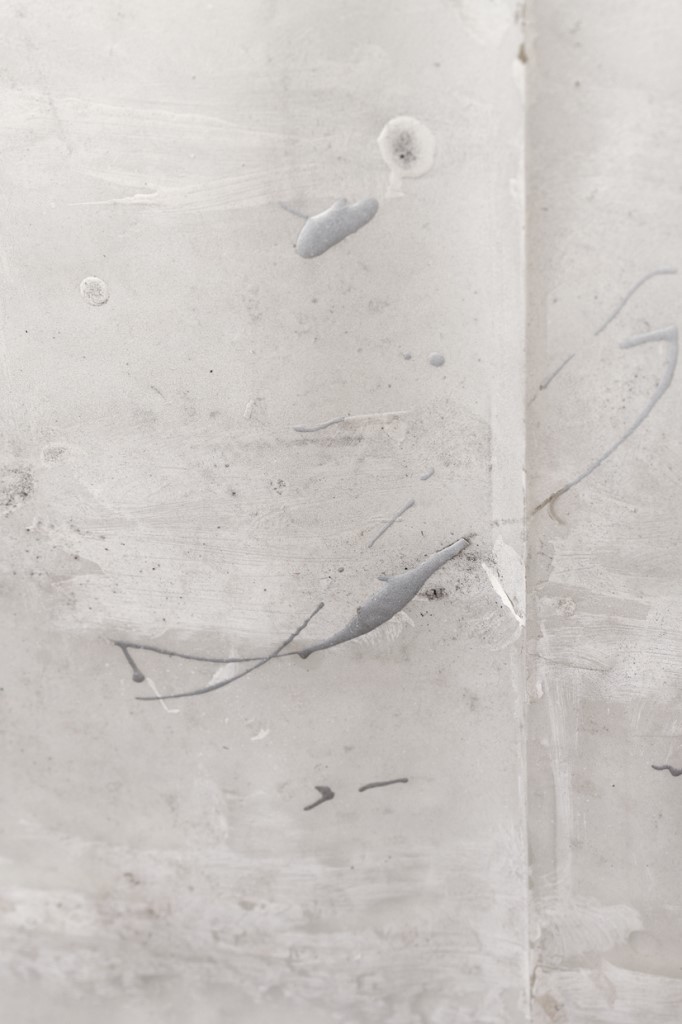

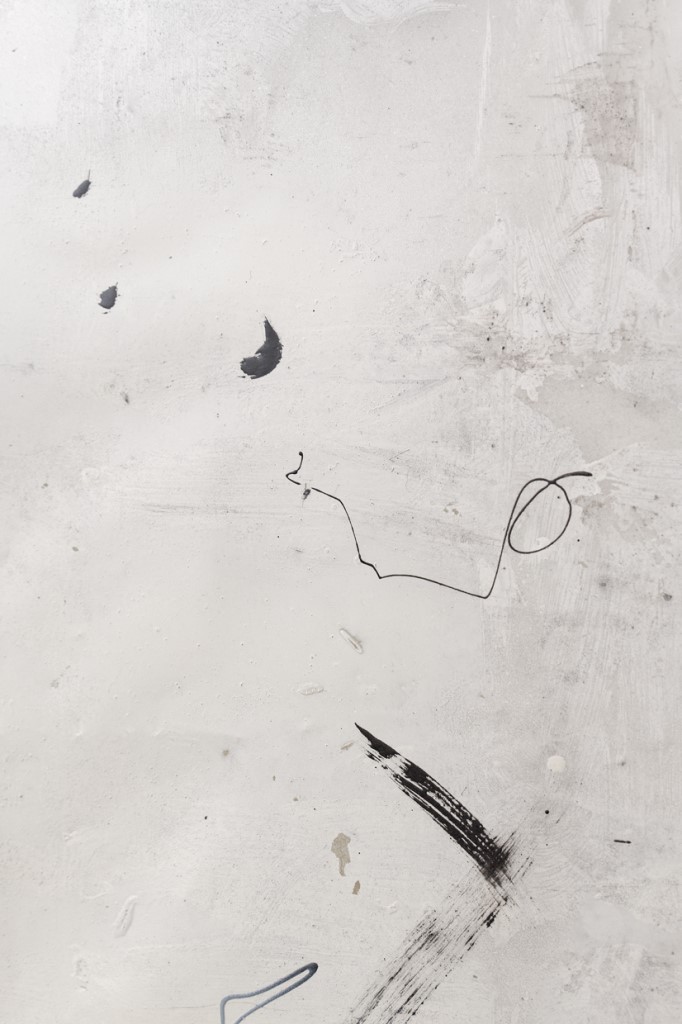

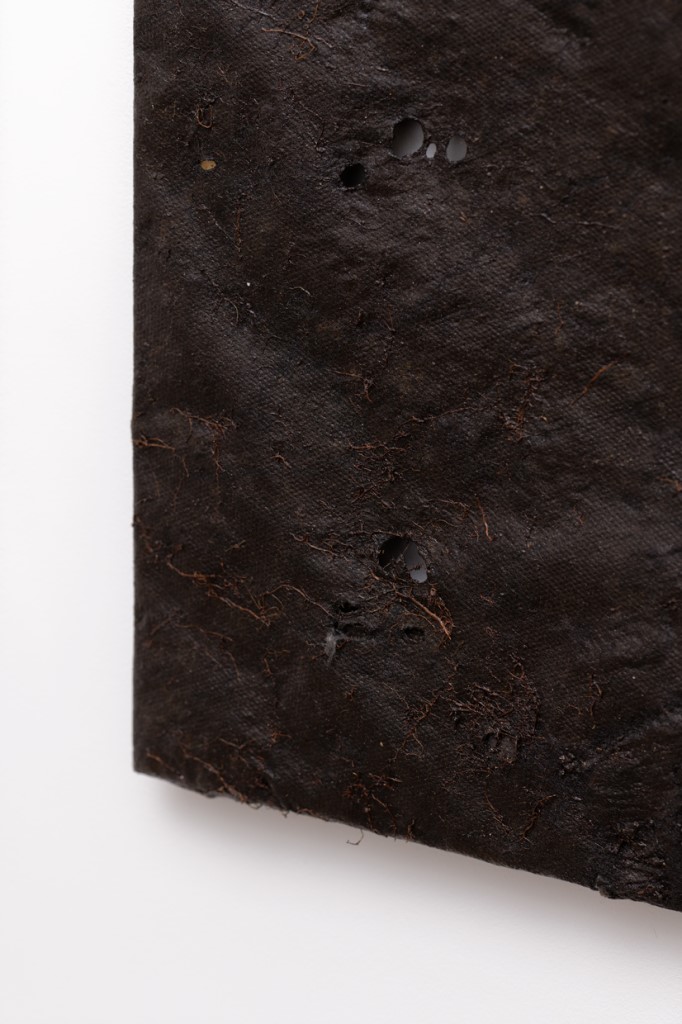

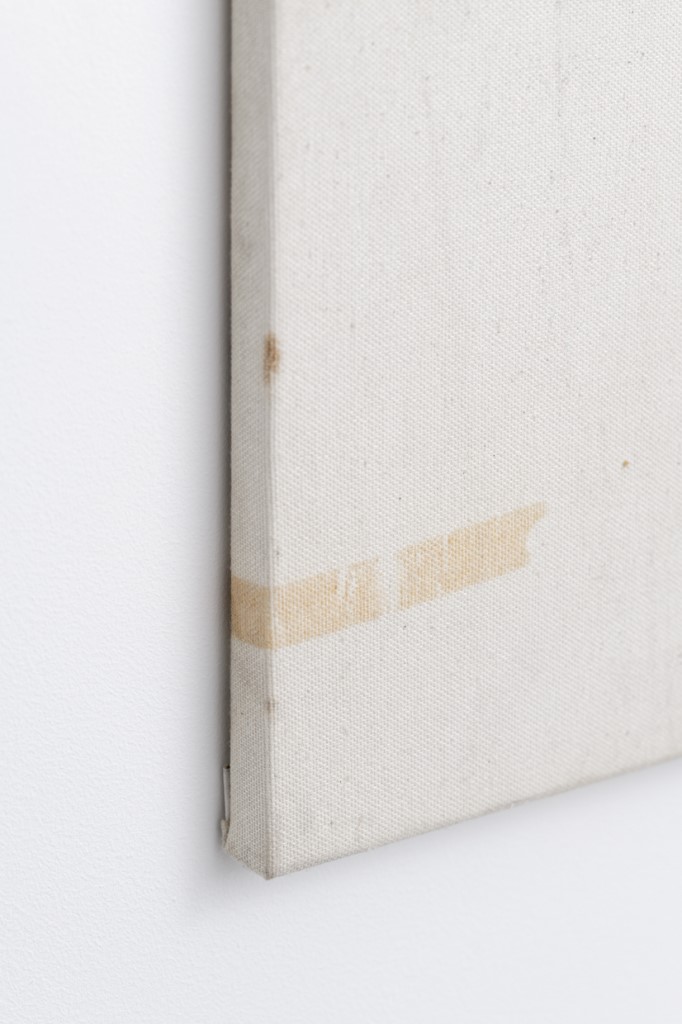

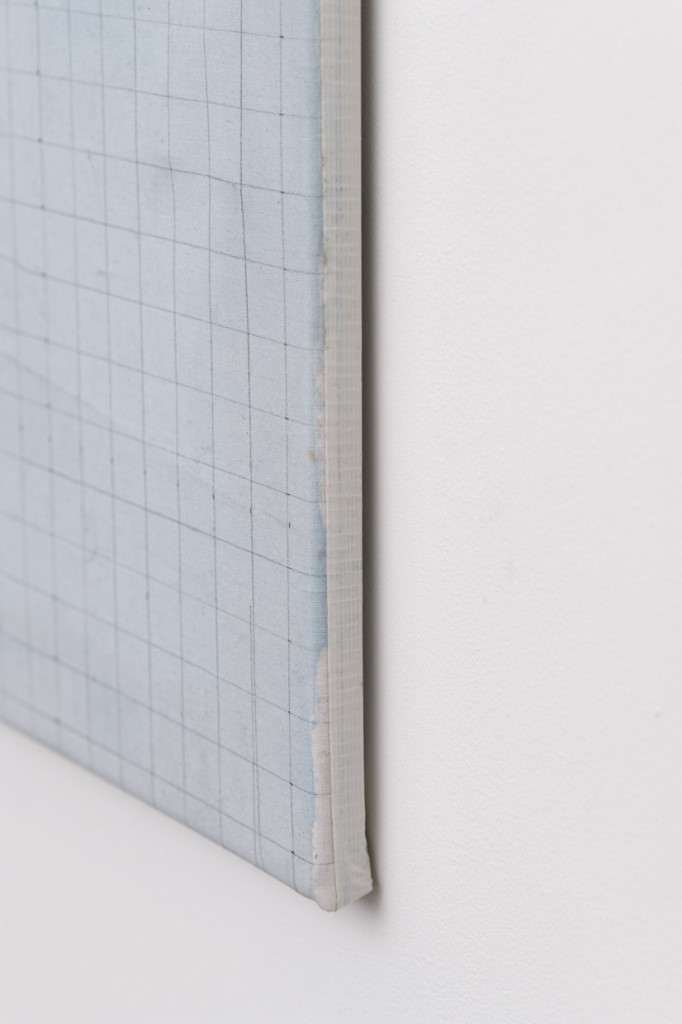

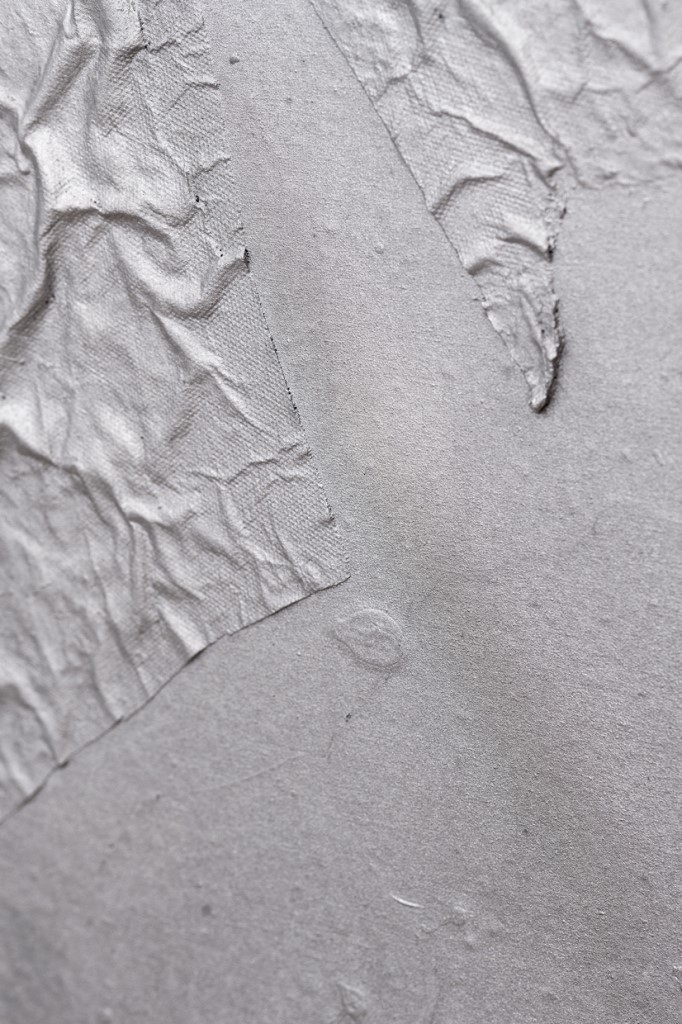

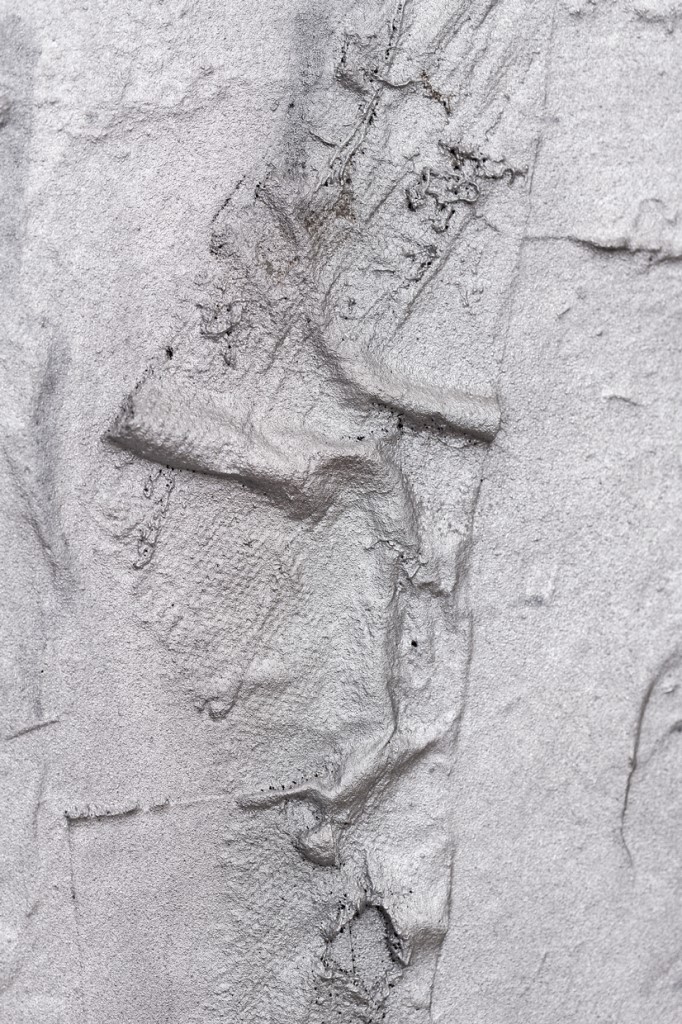

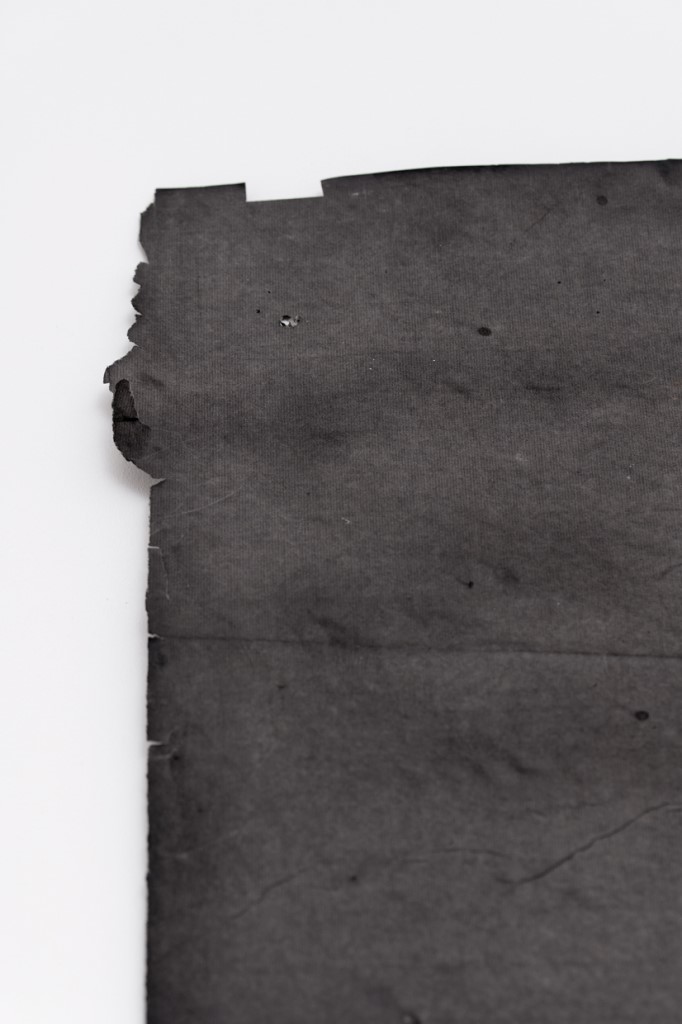

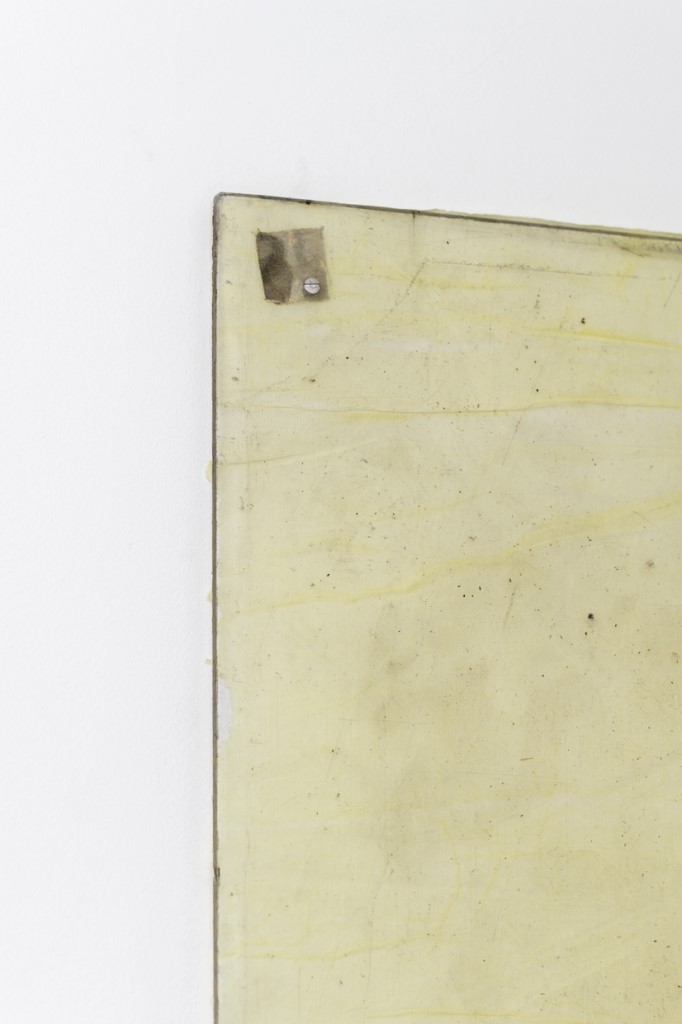

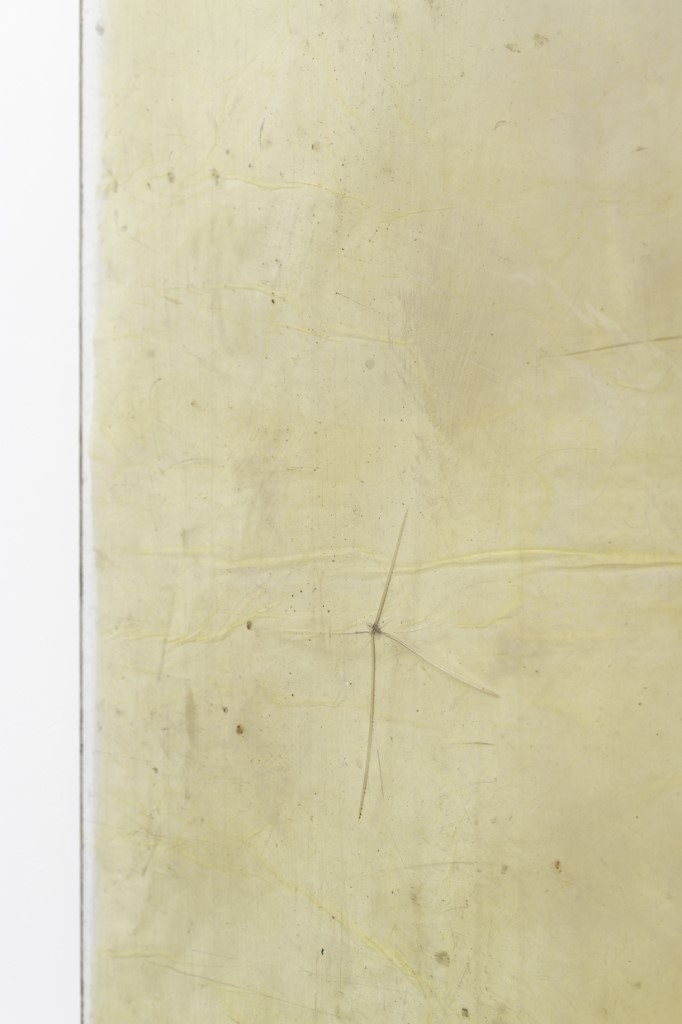

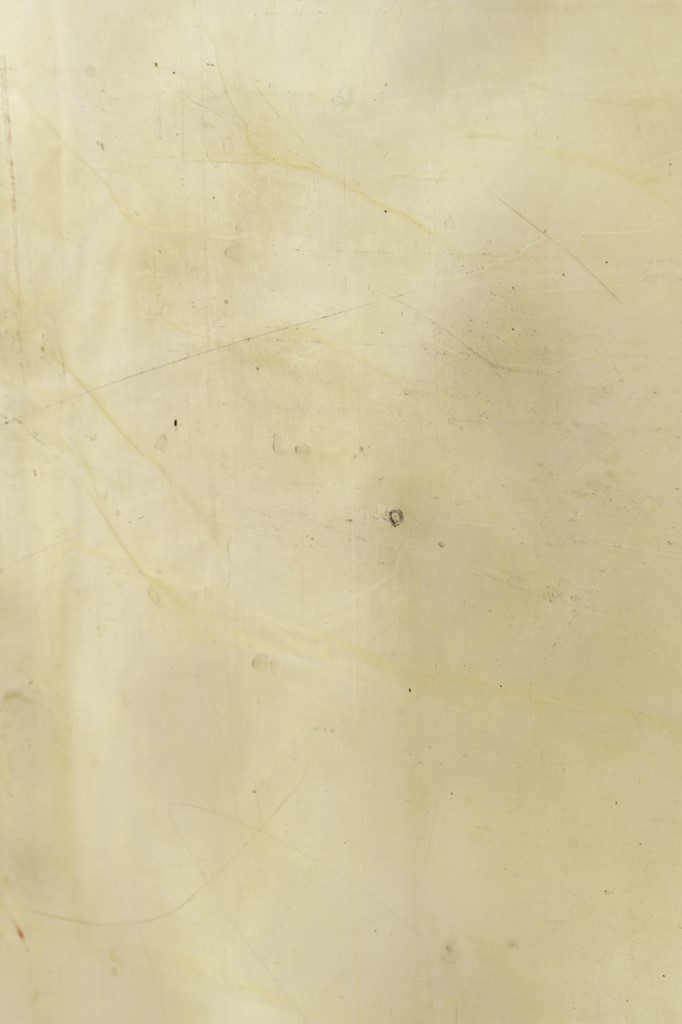

The attentive observation of Ian Kiaer's work, which he deliberately locates within the margins and endnotes of art history, provides an array of new relationships in the context of 21st century art that is more than ever marked by its integration into financial capitalism. Beyond this exchange value, whose financial liquidity presupposes a solid and determinate form, Kiaer's works raise the "question of what remains". What relationships between viewers, exhibition spaces, artworks, contemporary art buyers might arise in the "worlds under construction" we have now entered? How may we journey in what remains of painting, starting from the smallest possible signifier: the spot of pigment, the dust deposited on the canvas, the square grid pattern drawn with pencil, the aluminium trace of a work that no longer exists, the Plexiglas retrieved from the streets?

In studying 16th century Confucian painting, Kiaer noted that exiled scholars would turn to painting when denied a direct involvement with politics. Their painting became a different order of resistance, an alternative engagement. In reference to this, Kiaer views painting as less a matter of applying pigments on canvas than as a "surface of significance". The studio, central in this practice, is a waiting area where the works occur and are apprehended, rather than being intentionally made. They gradually emerge from the floor, almost as side thoughts released from the artist's will. Understood this way, the studio provides the ground for precarious and indeterminate arrangements that make life possible². Having reached the gallery space, these works continue to make relations with surrounding elements: the spacings between walls, the floor, the ceiling and one to another. They are thus never quite the same, and yet they provide a constant timbre, that of "the stuff of survival"³.

IA

¹ The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton University Press, 2015).

² "thinking through precarity makes it evident that indeterminacy also makes life possible" Anna Tsing, op.cit. Quote available at https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/119987.Anna_Lowenhaupt_Tsing

³ "changing with circumstances is the stuff of survival", ibid, 27

translation: Callisto Mc Nulty

Born in 1971 in London (UK), Ian Kiaer has exhibited internationally since 2000, with solo exhibitions at institutions including Tate Britain, London; Galleria Civica d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Turin; Kunstverein München, Munich; Fondazione Querini Stampalia, Venice; Centre International d'Art et de Paysage de Vassivière; Henry Moore Institute, Leeds; Musée d'Art moderne de la Ville de Paris; Kunsthalle Lingen and Heidelberger Kunstverein. He has also exhibited at the Venice Biennale (50th), Istanbul Biennale (10th), Berlin Biennale (4th), Lyon Bienniale (10th) and Manifesta 3.

For Roger, a dear and absent friend.

Warmest thanks to: François Orphelin, Annarosa Spina, Clovis Bataille, Inès Huergo and Colette Barbier (Fondation Pernod-Ricard), Anne Bonnin, Aurélie Voltz.

- -

Comme le matsutake, champignon japonais qui prospère dans les ruines du capitalisme, le travail de Ian Kiaer occupe depuis le début des années 2000 les vestiges de la peinture. Ses installations explorent comment le sali, le mis-au-rebut, l'accidentel, le rafistolé, le prélevé peuvent faire oeuvre.

L'anthropologue Anna Tsing décrit dans l'ouvrage Le Champignon de la fin du monde¹, la période anthropocène - qu'elle renomme capitalocène - comme une « vie sans promesse de stabilité ». Dans ce monde où la précarité est la norme, où la notion de progrès n'arrive plus à s'imposer, des agencements provisoires de vies minérales, animales, végétales et humaines s'installent au sein même des ruines produites par le capitalisme. Ces collaborations inédites sont tout sauf utopiques, elles prennent leur source dans l'ici et maintenant de l'état du monde, dans les forêts dévastées par l'exploitation intensive, dans la présence de populations déplacées par les guerres impérialistes.

L'observation attentive du travail de Ian Kiaer, qu'il place sciemment dans les marges et les notes de bas de page de l'histoire de l'art, offre un éventail de relations nouvelles dans le contexte de l'art du 21ème siècle plus que jamais marqué par son intégration au capitalisme financier. Hors de ces échanges de valeurs dont la liquidité financière présuppose une forme solide et déterminée, les oeuvres de Ian Kiaer posent « la question de ce qui reste ». Quelles relations entre spectateur·rice·s, espaces d'exposition, oeuvres et acheteur·euse·s d'art contemporain peuvent naître des « mondes en chantier » dans lesquels nous évoluons désormais ? Comment cheminer dans ce qu'il reste de la peinture, en partant du plus petit signifiant possible : la tache de pigment, la poussière déposée sur une toile, le quadrillage reporté au crayon, l'empreinte aluminium d'une oeuvre disparue, le plexiglas collecté dans la rue ?

En étudiant la peinture confucéenne du 16ème siècle, Ian Kiaer a observé que les artistes en exil peignaient quand on leur ôtait la possibilité de faire de la politique. Leur peinture devenait une résistance d'un autre ordre, un engagement alternatif. Ainsi, Ian Kiaer entend moins la peinture comme l'application de pigments sur une toile que comme « surface de signification ».

L'atelier, central dans la pratique de Ian Kiaer, est un espace de retraite et d'attente où les oeuvres arrivent (comme on le dit d'un accident) plus qu'elles ne sont conçues. Elles apparaissent petit à petit à partir du sol, presque malgré l'artiste, au gré d'un processus poétique à l'inverse des récits héroïques. L'atelier est l'endroit idéal des agencements précaires et indéterminés qui rendent la vie possible.² Parvenus à la galerie, ces assemblages continuent d'essayer de s'unir avec les éléments en présence : les murs, le sol, le plafond, et entre eux. Les oeuvres ne sont donc jamais exactement les mêmes, et pourtant, elles ont comme un parfum commun, celui du terreau de la survie³.

IA

¹ Le Champignon de la fin du monde. Sur la possibilité de vie dans les ruines du capitalisme, éd. La découverte, Paris, 2015.

² « penser avec la précarité fait que l'indétermination rend aussi la vie possible » Anna Tsing, op.cit., p.56

³ « changer en fonction de la circonstance est le terreau de la survie », ibid., p.65

Ian Kiaer est né en 1971 à Londres (Royaume-Uni). Depuis 2000, il montre son travail à l'échelle internationale dans le cadre d'expositions personnelles au sein d'institutions telles que la Tate Britain à Londres, la Galleria Civica d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea à Turin, le Kunstverein à Munich, la Fondazione Querini Stampalia à Venise, le Centre International d'Art et de Paysage de Vassivière, Henry Moore Institute à Leeds, le Musée d'Art moderne de la Ville de Paris, la Kunsthalle de Lingen et le Heidelberger Kunstverein. Il a également exposé à la 50e Biennale de Venise, à la 10e Biennale d'Istanbul, à la 4e Biennale de Berlin, à la 10e Biennale de Lyon et à Manifesta 3.

Pensées pour Roger, cher ami absent.

Remerciements chaleureux à : François Orphelin, Annarosa Spina, Clovis Bataille, Inès Huergo et Colette Barbier (Fondation Pernod-Ricard), Anne Bonnin, Aurélie Voltz.